|

Think of African beads and two images come to

mind: the first, glass trading beads brought from Venice and used in

the slave trade, and second, the tiny beads from the Czech Republic,

used by myriad African tribal peoples, including the Maasai, Samburu,

Zulu, and Yoruba. But there are also glass beads made in Africa, and

used by Africans, and these have a rich heritage, too. They are

found in one small area of Ghana, commonly known as the Gold Coast

among those who learned history before 1957. Located along the

coastline of Africa's northwestern "hump," Ghana is a

country of great heat, humidity, and cultural history.

On a continent often thought to be

unsophisticated in its material culture, Ghana artisans have

demonstrated a dazzling use of pattern and material in an abundant

range of crafts, from textiles to gold. It is here where the Asante

(also spelled Ashanti) flourished; it is the land of Kente cloth and

the famous Asante gold weights. The Asante culture was built around

a rich tradition often expressed in proverbs - proverbs that have

been condensed into single symbols that have meaning for the Asante.

Many of the universally understood symbols came to be fashioned

into gold weights. Gold weights (actually usually made of brass),

were needed in a culture in which gold dust was the medium of

exchange, the daily currency. Each merchant carried his personal set

of gold weights, usually 12 in all. There came to be thousands of

motifs in use, including porcupines, which represent the strength of

the warriors, the groundnut, a basic food, and the popular wari

board game, also known as mancala.

The kingdom was built on gold; the precious

metal was abundant and, as is often the case in African material

culture, the material at hand became the material of use. Gold

ornamentation, however, was restricted for royal use, although

perhaps restricted is not quite the right word. Within the

quite extensive royal community, gold was used lavishly to create

ornaments of astonishing variety and detail. It was used to such an

extent that when the Asantehene, the king of the Asante, was

on ceremonial display, he had to be carried - the weight of his gold

ornaments, the bracelets on his arms and legs, made it impossible

for him to move on his own. His staff was gold, the cloth he wore

included woven gold threads, his headpiece was of gold, his

daughters' faces were dusted and decorated with gold. The brilliant

yellow color of gold, the color that seems to capture the sun itself,

was reflected everywhere in the already brilliant sunshine of the

Gold Coast.

CEREMONIAL ROLE. But

the Asante gold-based culture is limited to the one area. In

the southeastern part of Ghana, a more humble object has become the

heart of the material culture. One of the oldest cultures, the

Dipo-Krobo people, part of the Ga-Adangbe linguistic group, claims a

small territory, no more than 70 miles from east to west and from

north to south. The heart of this cultural region is the village of

Odumase-Krobo, a drive of about 1 1/2 hours from Accra, on one of

Ghana's best roads. People such as the Krobo, who live close to the

coast, have come into contact with foreigners, both those from other

African cultures as well as Europeans. This has influenced their

language and some of their economic activities, but their

traditional cultural practices have managed to survive.

Each

year, the Dipo-Krobo festival takes place, a very old tradition

among the Krobo people. The ritual marks the coming of age of Dipo

girls, and strands of glass beads play a large role. The villagers

prepare for the ritual for an entire year; during the ceremony,

which takes place over several days, the girls wear different

strands of colored beads and are redressed several times, exchanging

one color for another. Although each girl is draped in many strands

of beads, these likely are not her personal property. A woman

acquires beads throughout her life, and wears them proudly - some

she will receive from her mother, some she will buy for herself as

she can afford them, and some will be given to her by her

husband when she marries. During the ceremony, the girls stay

together, secluded from the other members of the group. In the past,

the ritual was a crucial step leading to marriage; the girls

would be instructed in the ways of their people, learning about the

moral and ethical rules and how to fit into their culture. Each

year, the Dipo-Krobo festival takes place, a very old tradition

among the Krobo people. The ritual marks the coming of age of Dipo

girls, and strands of glass beads play a large role. The villagers

prepare for the ritual for an entire year; during the ceremony,

which takes place over several days, the girls wear different

strands of colored beads and are redressed several times, exchanging

one color for another. Although each girl is draped in many strands

of beads, these likely are not her personal property. A woman

acquires beads throughout her life, and wears them proudly - some

she will receive from her mother, some she will buy for herself as

she can afford them, and some will be given to her by her

husband when she marries. During the ceremony, the girls stay

together, secluded from the other members of the group. In the past,

the ritual was a crucial step leading to marriage; the girls

would be instructed in the ways of their people, learning about the

moral and ethical rules and how to fit into their culture.

At the culmination of this ceremony, a girl

would be considered eligible for marriage and indeed, in the past,

would be married immediately and leave with her husband for her new

life. Traditionally, a husband could take his intended away when she

was just 14 or 15 years old, but times have changed. These days, a

potential husband must carve out his own farm before he can marry

and he must pay a dowry to the bride's family. Equally important,

girls once considered to be of marriageable age are now more likely

to be attending school. The ceremony interrupts their schooling for

several days, but when the ceremony is concluded, the girl will

likely return to school and continue her education rather than

taking up her duties as a very young wife.

The festival usually takes place in April, but

the date is not fixed and changes from year to year. The chief

determines when the ceremony will start, and it can be delayed for

several reasons - the moon may not be in the right position, for

example, or the chief may not have gotten enough money together to

pay for all the food needed to take care of the many people who come

to take part in the ceremony.

Originally, participation in the ritual was

strictly limited to pubescent girls. Today, however, if a

participating teenage girl has a younger sister, the little one will

take part as well, even though she is not considered ready for

marriage by any standard - a practical response to the enormous

expense involved in staging the ceremony. Because of the costs,

there is always the chance that the ceremony might not take place

when the younger sister comes of age and so she takes her place in

the event even when it is not really appropriate. Although the

ceremony is restricted to women, men may observe it; in many

cultures, coming of age ceremonies are limited to the one sex.

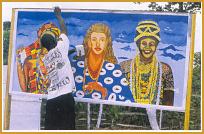

THE LOST-STRAW METHOD. The

beads are made by hand in Odumase- Krobo village using an age-old

glass making method, although today, the basic material comes from

recycled glass, mainly from imported bottles. The chief beadmaker is

a man named Nomada Djaba, known locally as Cedi (pronounced CD).

Whether by design or by coincidence, "Cedi" is also the

name of the currency in Ghana.

Before

the bead making begins, Cedi and his helper form small, round, clay

molds that are baked in a kiln. Then the glass bottles are ground

into a fine powder which is poured, layer by layer, into five

rounded depressions in the molds. Before

the bead making begins, Cedi and his helper form small, round, clay

molds that are baked in a kiln. Then the glass bottles are ground

into a fine powder which is poured, layer by layer, into five

rounded depressions in the molds.

For varied-color glass, two or more layers of

different colors are used, then a sharp tool similar to an ice pick

is used to draw the color through the mixture. When the section is

filled, a straw is placed in the center of each mound of powdered

glass; during the firing, the straw burns out, leaving behind a hole

for stringing the beads. (One may call this the 'lost straw' method,

similar to the lost-wax method of casting gold.) After the beads are

fired and allowed to cool, they are washed in order to remove the

residue from the kiln. Finally, the beads are strung onto sisal or

other fibers to form long ropes.

The appearance of the beads varies from opaque

to translucent. Colors range from pale pastels to vibrant primary

colors. In addition to matte-finish, translucent beads of one solid

color, the bead maker offers variegated colored beads that may

include blue and green in the same bead. Some beads are completely

opaque with a shiny glazelike finish, while others include central

stripes decorated with bits of glittery sand. These are well

finished and are smooth to the touch. Not one of the beads is truly

round; they are more like cushions with slightly flat ends where

they are strung together. Strands are generally comprised of just

one color or type of bead, that is, the decorated beads are not

mixed with the monochromatic beads. According to Lois Dubin's History

of Beads, making beads using powdered glass is a technique

nearly unique to Africa. The practice has reached a remarkable level

of sophistication since it began, estimated to be some time in the

16th century.

Glass bead making in sub-Saharan Africa is

confined to a small area of West Africa in the countries known today

as Niger, Nigeria, and Ghana. But bead making is not an industry or

even a widely practiced craft, instead usually confined to a group

of families. Glass making in Ghana, specifically in the region where

the Dipo-Krobo people live, is a 'dedicated' craft, aimed at, and

guided by, the needs and demands of the local people; the people

need the beads for their ceremonies as much as they enjoy wearing

them. The makers and the initial consumers are all found in the same

town, and the beads are created almost to order by a small number of

craftsmen in one-man workshops.

Cedi, however, also sells beads to visitors

who make their way to his own little shop. Outsiders are obvious, as

they usually come accompanied by a guide who knows the bead maker

and knows the way. On one of our more recent visits, the Italian

ambassador to Ghana and his family were also there, making their

choices. Some of Cedi's beads are sold in the local market, and he

also travels to Europe and the United States to sell his work. Cedi, however, also sells beads to visitors

who make their way to his own little shop. Outsiders are obvious, as

they usually come accompanied by a guide who knows the bead maker

and knows the way. On one of our more recent visits, the Italian

ambassador to Ghana and his family were also there, making their

choices. Some of Cedi's beads are sold in the local market, and he

also travels to Europe and the United States to sell his work.

Because the beads are made individually, the

colors can be varied at will, unlike the tiny, mass-produced glass

beads from the Czech Republic that are favored so widely in other

African cultures. Where the availability of the Czech-made beads

depends on the middlemen, usually Asian entrepreneurs, who bring

them to the markets in the many areas of Africa where they are used,

the color of the Ghanaian beads is dictated by the scarcity or

availability of the recycled glass. Certain colors are difficult to

obtain or not available at all.

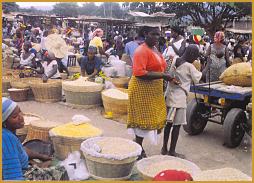

In rural Africa, open-air markets take

the place of supermarkets. In Odumasi-Krobo, a sprawling market

takes place twice a week. Early in the morning on market days,

vendors arrive and spread out their merchandise. The goods - whether

they are food, fabric, or furniture - become the display. A walk

through the local market takes the shopper past stalls offering

chickens and goats, vegetables and sandals, hair cuts and cooking

pots, anything and everything people in this area need. The bead

shopper must know exactly where to go. The bead sellers are tucked

into one small area of the market, reached only after a circuitous

path through the maze-like aisles. Although there are no set

prices in most places, and no price tags or signs, local people who

buy the same goods each week know the prices, and a little friendly

discussion is all that's needed to agree on a price. In rural Africa, open-air markets take

the place of supermarkets. In Odumasi-Krobo, a sprawling market

takes place twice a week. Early in the morning on market days,

vendors arrive and spread out their merchandise. The goods - whether

they are food, fabric, or furniture - become the display. A walk

through the local market takes the shopper past stalls offering

chickens and goats, vegetables and sandals, hair cuts and cooking

pots, anything and everything people in this area need. The bead

shopper must know exactly where to go. The bead sellers are tucked

into one small area of the market, reached only after a circuitous

path through the maze-like aisles. Although there are no set

prices in most places, and no price tags or signs, local people who

buy the same goods each week know the prices, and a little friendly

discussion is all that's needed to agree on a price.

Ghana offers a look at the "real"

Africa, where traditions are alive and where cultural expression is

part of daily life, not something performed for curious visitors.

These strands of glass beads are part of that expression, a

continuation of an ancient tradition. They also speak to the

universal love of adornment.

For more photos by Jason

Lauré visit his website at http://www.agpix.com/africatrek |