|

After 32 years as a Black man in America, I finally journeyed back to the Motherland. I am a high school teacher in Northern California and during the summer of 2003, I went to Ghana, West Africa, for a month to explore education and attempt to connect with a history and an existence that I’ve only read in books. Although I knew my trip would be intense, I had no idea it would be as life changing as it was. The following is not an actual chronicle of my trip (I did a great many things), but instead is a combination of journal entries and emails that explore my own personal experience and emotional journey. After 32 years as a Black man in America, I finally journeyed back to the Motherland. I am a high school teacher in Northern California and during the summer of 2003, I went to Ghana, West Africa, for a month to explore education and attempt to connect with a history and an existence that I’ve only read in books. Although I knew my trip would be intense, I had no idea it would be as life changing as it was. The following is not an actual chronicle of my trip (I did a great many things), but instead is a combination of journal entries and emails that explore my own personal experience and emotional journey.

I have to admit that, although I had always longed to go to Africa, I had always been a bit apprehensive about actually going. I mean, after all, we are no longer Africans in the true sense, right? Through slavery and mixing and the American Dream, we have become something else – homeless half-breeds who have taken up residence in unfriendly territory. “Africa for Africans” – Is that really realistic? I never lived in Africa, nor did my parents or their parents. I have heard so many stories of people who “go home” and are not seen as a member of the community, but as an “American.” (Is home really home if you’ve never lived there)? On my trip, I reread Langston Hughes’ autobiography,

The Big Sea, and was reminded of his words:

“And further down the coast it was more like the Africa I had dreamed about – wild and lovely, the people dark and beautiful, the palm trees tall, the sun bright, and the rivers deep. The great Africa of my dreams!

But there was one thing that hurt me a lot when I talked with people. The Africans looked at me and would not believe I was a Negro.

You see, unfortunately, I am not Black. There are lots of different kinds of blood in our family. But here in the United States, the word “Negro” is used to mean anyone who has any Negro blood at all in his veins. In Africa, the word is more pure. It means all Negro, therefore black.” |

But other Blacks who had been to Ghana told me differently. They said that everyone they met said, “welcome home” and that every Black American should go. So, I put my faith in the Diaspora and got on the plane.

I changed planes in London and I immediately felt different, somehow. All my nervousness and apprehension disappeared when I saw all of the Africans boarding the plane. I was overwhelmed with an extreme sense of comfort that is somewhat indescribable, as if, for the first time in my life, I could finally take a breath.

Soon I was coming into Accra, Ghana, West Africa. When the plane landed, I turned to the back page of Hughes’

The Big Sea and wrote:

“8:30pm. Touchdown. 7/15/03 – 17 hours of flying. 79o and raining.

I am here! We just touched down on the Motherland. I am in Africa. I never thought I would ever be here. I thought that it was just a place I would dream about, but never see. A place where white people go to steal things. But, I feel like I am somehow taking it back. The entire plane clapped when we touched down, as if they were so happy to be “home.” I am happy too, and I haven’t even gotten off the plane.”

Once I landed, I immediately wondered why it had taken me so long to come to Africa. There is no need to fear. Everyone I met said, “welcome home” and suggested that regardless of my existence in America, I am originally an African, and therefore still an African. (I thought that this would be a very overwhelming concept, but it was not too overwhelming; it just made sense).

One of the first things I noticed about Ghana was the names. At least half of the people I met seemed to have “American” names like Bob, Vicki, Rodney, and Ben. At first, I thought that people might be translating their name for me (the stupid American) so that it would be easier for me to say their name. However, I soon learned that that wasn’t the case. First of all, although there seems to be around 45 official languages in Ghana, the national language is English (this seems to be based on a history of colonialism and the difficulty of agreeing on a national native language). In addition to this, around 90% of the country is Christian. When a child is born in Ghana, they take on a name based on the day of the week on which they were born. For instance, I was born on a bright, sunny Sunday morning. So, my Ghanaian name would be

Kwesi, which means a male born on Sunday. You might be thinking that it would create a lot of confusion if there were essentially only 7 names for boys and 7 names for girls. So, after 8 days, there is a naming ceremony in which the baby is usually given a secular or “Christian” name, hence the somewhat “American” names.

On the same track as the names, one of the most intense and enlightening experiences happened in the first week of my trip when I went to visit the Nungua Secondary School. There, I met a teacher who asked me my name. When I told her that my name is Anthony Delaney, she smiled and asked me if I knew what my name means. I didn’t really get it. No, I had no idea what my name means, and how would she know what my name means. She went on to tell me that I am I am Ewe (a Ghanaian tribe) and my name comes from that tribe. She said that she actually thought this before she asked me because I “look” Ewe because I have Ewe facial features. She went on to say that my last name, Delaney, means, “The Savior has given it.” In Ewe, it would be spelled ”Delane.” “Dela” is a traditional Ewe word that means “savior” and then there are multiple endings that create a phrase. Her name is

Delali, which means “(my) Savior exists.” She is, of course, also Ewe.

Now, let me backtrack a minute and say that my choice to go to Ghana was based mainly on hearing about an interesting cultural center in Ghana called the Dagbe Cultural Center in

Kopeyia. There was a time when I tried to trace my roots, but never got much past my grandfather on my father’s side. It never even occurred to me that I could search for my roots in Africa, let alone that I might just unwittingly stumble across my native roots. But then I thought about the fact that that the Trans-Atlantic slave trade came mainly through the Gold Coast, and therefore, most slaves were Ghanaian, making most Blacks in America who are descendants of slaves Ghanaian. The implications of this are amazing. Most slaves took on their slave master’s name and many changed their names entirely after slavery. This suggests that either my family kept and preserved their African name through slavery or regained it after slavery (or that my family were never slaves to begin with, but rather free Blacks. Huh). Now, the name itself tripped me out, but it did not totally convince me that I was a direct descendant of the Ewe tribe. What did convince me were the numerous unsolicited comments that I received throughout the rest of my trip about how I look very Ewe. These were all stated before they had even heard my last name.

Although it was amazing to feel like “family,” it also came with a heavy burden. I felt like I was the one person that went away and got something else. It’s not necessarily that people felt like I had “escaped” Ghana and gone to a “better place;” there is great African pride in Ghana. It’s as if I was the one child in the family that was sent to school and was expected to do great things and then come back and bring up the family. It’s not that people feel that living in the land of white people is better, it simply offers you more opportunities.

While in Ghana, I felt like I was charged with two things. The first of which was to properly represent Ghana, Ghanaians, Africa and Africans to Black Americans. I sat with people who told me stories and history so that I could bring it all back with me and tell “the others.” I sat with people who wanted to personally take me everywhere and show me the beauty of Ghana so that I could come home and show that beauty to other Blacks. Many Ghanaians whom I spoke with have a just fear that Africa has been misrepresented. Sure, many Blacks in American want to visit Africa, but how many people truly want to leave the familiarity of the US and live for the rest of their lives in a developing country like Ghana? We (yes, Black people, too) have been raised with images and stories that tell us that Africa is savage, dirty, uncivilized and primitive. People only live in villages and walk around without clothes on and without any sense of common decency. We have been told that the only people that go to live in Africa are white missionaries, white peace-corps workers or rich white people on safari (interested in that wild, untamed Africa). Yes, we are interested in visiting the land of our ancestors, but do we really want to live like them? The answer is yes. There is a purity in the human spirit in Ghana that I have never felt in the US. There is a safety on the streets that I have never felt in my own home in the US. I sat with men who showed me that Africa is indeed the Promised Land. It is indeed the paradise spoken of in the bible. I don’t mean the white-beaches-and-coconut kind of paradise. Yes, that’s what you’ll see if you just look on the surface (and if you’re conscious, that simplicity will disappoint you). I’m talking about something deeper. Something deep in the skin. As if something was left in our blood. Something that calls at a frequency even dogs can’t hear. Something that here, in the US, connects to nothing, but, in Ghana, surrounded by black faces in the market, in the government, on TV, on billboards, in adds, as teachers, politicians, athletes, mentors, tutors, mothers, fathers, children, rich and poor, good and bad… there is finally a response and an interplay that is unimaginable. I truly believe that all Black Americans should experience their motherland. Because, it’s important.

So, I have begun to play my part. I am reaching out and calling all Black Americans back to Africa. But, therein lies my second task, which is to save Ghana. One of the more unfortunate parts of my trip was the ultimate poverty and level of desperation that exists in so many Ghanaians. Now, I have been told numerous times not to think that all Ghanaians are poor, because there are some very wealthy Ghanaians. I am sure that this is true. In my month in Ghana, I don’t believe I ever met any “very wealthy Ghanaians” nor did I see any sign of them except in the $300-a-night hotels and on the “tourist” boat that cruises Lake Volta. I am not an economist; I am a humanist. What’s the point in talking about wealth in Ghana if it doesn’t filter to the majority of the people who live there. I feel like there is a some secret, hidden VIP lounge (which may be the hotels) somewhere in Ghana where all the rich people live and shop and throw parities, because I didn’t see any sign of them in the lives of the average person. So, if you are a Black man from America who can afford to travel to Africa for a month (and, thank you to my school for paying part of my trip), then you are seen as something special. Let me explain it this way, in Ghana, one beer costs around 6,000

cedi. At the time that I was there, $1 (US) equaled around 8885 cedi (but the rate changes everyday). So one beer cost less than a dollar. And, you are a Ghanaian who is lucky enough to have a job and you only make $50 a paycheck and then you have these tourist who are changing $100 and $200 EVERY DAY. Until 2002, the largest bill was 5,000 cedi (side note - I went to the national museum and they had the history of Ghanaian money. The most recent money in the museum was from 1976 were 1 and 2 cedi bills. Now, 27 years later, the smallest bill available is 1,000

cedi. Imagine watching the dollar plummet at that rate in the span of your current lifetime). Anyway, They just introduced 10,000 and 20,000 cedi bills, but the majority of large bills are still in 5,000 cedi bills. So, if you cash $200 in traveler’s checks, you receive 17,77000

cedi, which gives you about 355 bills. You literally receive so many bills that you can’t even fit them in your pocket or your money pouch. This is an obscene amount of money for the average Ghanaian.

So, let’s remember that I am not a white tourist that you want to pressure for dash or a tip. I am that distant relative who was “sent off” to live in America and is now charged with “giving back to the family.” I am expected to buy land and set up a business and invest in the future and help out a village and build a school and marry a Ghanaian and change the world and save Ghana. And, the most difficult part of this is that I wanted to do it all. The difficult thing is that I “feel” like family and I do have more and I do want to help and, realistically, I can and should. Yes, I would like to buy some land and pay a farmer. Yes I would like to help out a village and a youth center, especially when $50 is a huge sum of money to most. I really struggled (and still struggle) with this whole thing. At one point, I bought some beads and wore them only once. Every one was so enamored by the beads because they can’t afford them - ancient beads that can no longer be made - but I could buy them on a whim because they cost less than $20 US. I unwittingly purchased an IRREPLACEABLE piece of African history for the price of a hamburger, fries and a Budweiser just because I thought that they were “pretty.” You can tell the tourist because they wear beads. It seemed like most Ghanaians had beads, but only wore them on special occasions because they are “expensive” (like pearls or fine jewelry).

This whole struggle honestly brings tears to my eyes. People who have taken care of me everyday are now looking at me as some kind of a savior, someone who is family and can help - not them, but everybody. Conversations with proud Africans who want to tell me everything because I am family and I am expected to tell the “truth” about Africa and encourage more Blacks to return to Africa. I am expected to start up a village farm because I am family and I have more so, I should help. I am sought after by women because I am family and their mothers would like me because I am really Ewe.

I have been around the US and traveled to Mexico, Jamaica and also to Europe many times, but I am truly in a unique place now; a developing country with billions of dollars in resources (gold, diamonds, timber, etc.) that never make it to the common man/woman and a country that is also caught between tradition/pride, western life and money. Babylon has destroyed everything. Paradise is lost. In then end I am left struggling, looking into a beautiful woman’s eyes and saying, “No, I’m sorry, but I do not want to marry you.”

An email

Sent: Saturday, July 26, 2003 8:55 AM

Subject: The Slave Castle

Friends, Friends,

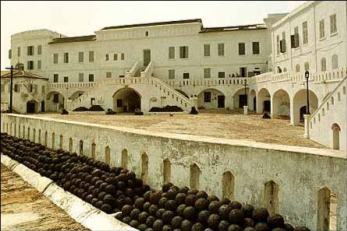

Yesterday, I went to one of the Slave Castles. Slave Castle in itself sounds like an oxymoron to me. How can something as grand as a castle exists for something as horrific as slavery? Well, it does. The huge castles are scattered throughout this area and were used to house slaves (up to 1200 or 1500 in some castles) in deep dungeons. There are so many things about them. It is a very sad memorial. You can literally feel the spirits of the past as you walk though the dungeons. There are still scratch marks embedded in the walls and ground still feels like blood and urine and suffocation and fear.

One of the most disturbing parts for me was stepping into the “cell.” In the literature of the Cape Coast Castle it says:

“This cell is often referred to as the condemned cell at the castle. It is believed from a historical point of view that some of the captives revolted against the European Merchants because of the ordeal in which they were subjected. Among those found uncontrollable were either branded or died of suffocation and starvation to serve as a deterrent to others. “This cell is often referred to as the condemned cell at the castle. It is believed from a historical point of view that some of the captives revolted against the European Merchants because of the ordeal in which they were subjected. Among those found uncontrollable were either branded or died of suffocation and starvation to serve as a deterrent to others.

As many as fifty people were confined to that small cell. They died so painfully that some scratched the floor and the walls. After death, they were given mass burial or as being speculated, thrown to sea.” |

I immediately felt nauseous and claustrophobic and had to leave.

There is a door in the castle called the “Door of No Return.” This was the final exit for the African Slaves and they boarded boats across the Middle Passage. In 1998, Ghana celebrated the Emancipation Day by exhuming two skeletons from New York and Jamaica bringing them back to Africa. They brought the skeletons back through this door and had a ceremony and marked it as the “Door of Return.” The literature says,

“with that ceremony, we the living are welcoming our brothers and sisters in Diaspora back home.” When I visited, we went out the “Door of No Return” to the landing just outside the door. There were a number of Ghanaian fisherman and children bringing in boats and mending nets. Once on the outside, we saw the new “Door of Return” sign and then re-entered the castle through the door. After we were back inside and walking away, and the big wooden door was closed, we heard a small voice calling out from the other side of the door. The small voice cried “Hello! Can anybody hear me?” It was probably just a child calling after the Americans, but there was an odd tinge of desperation in the voice. The castle was eerie enough, but that experience was too spooky to forget. A week or so later, I wrote this poem (this is unfinished - raw and unrevised –it will get better):

Sankofa

I lived through an African rainstorm

Traces of history rolling through the mud lined streets

If you stand on the shores of Cape Coast

You will hear slave

Voices in the wind crying “Hello,

Can anybody hear me?” (Yes, I can)

Back home

In the states

There are ghosts of slaves

Wearing dreadlocks

And 3-piece suits

Clutching cowries

And bargaining for their lives –

The auction block is far away, now

But our shackles keep us tethered

(but, I am a runaway).

Africa for Africans, Garvey said

Sankofa

-Return to your roots, and the rivers

Langston spoke of at 18

Return to this mud

And the rain and the Black earth

Under my fingernails

(And under his skin).

“We are all Africans,” Malik said

Over a Star at the Blue Blue in Nungua

Retrace the rivers and the mud and the rain

Gather more

And return to your roots.

Open your mouth

And drink the rain

It is manna

And this is Paradise. |

One thing that dawned on me while at that Slave Castles was that in coming to Africa, I thought that slavery would be seeping out of every crack in the sidewalk, but it’s not. I feel like Africans see slavery as a distant and sad piece of the country’s history. It’s as if African-Americans are more connected or fixated on slavery than Africans. I thought it would be the opposite, but it really makes sense when you think about it. African-Americans exist as a literal product of slavery while contemporary Africans exist in spite of slavery. Africans still have their culture, fluently speak their native language and know their home and their ancestors, etc., while African-American’s are a peoples without a home. We are estranged, but contemporary Africans never left their homeland. So, because of all of this, in Africa, slavery seems like a piece of history that they are trying to understand, but for African-Americans, it is a reality that we are still struggling to overcome. One thing that dawned on me while at that Slave Castles was that in coming to Africa, I thought that slavery would be seeping out of every crack in the sidewalk, but it’s not. I feel like Africans see slavery as a distant and sad piece of the country’s history. It’s as if African-Americans are more connected or fixated on slavery than Africans. I thought it would be the opposite, but it really makes sense when you think about it. African-Americans exist as a literal product of slavery while contemporary Africans exist in spite of slavery. Africans still have their culture, fluently speak their native language and know their home and their ancestors, etc., while African-American’s are a peoples without a home. We are estranged, but contemporary Africans never left their homeland. So, because of all of this, in Africa, slavery seems like a piece of history that they are trying to understand, but for African-Americans, it is a reality that we are still struggling to overcome.

The biggest thing that I learned about the slave castles is that I never want to go back to them.

I spent about 3 and 1/2 days in the village of Kopeyia at the Dagbe Cultural Center attempting to learn traditional drumming. It was very hard for me. I had two 2-hour lessons per day and I am horrible. The hardest part for me is the timing because the entire sound is based on the offbeat. American music is rooted in the downbeat and the 4/4 timing. Here, everything is polyrhythmic and played OFF of the downbeat and in 5/6 or 6/8 time. I have equated it to snowboarding - when I first started snowboarding, I spent 3 days on the slopes falling down and getting beaten up, sore and frustrated. I later came back to it and enjoyed myself. Here, I spent 3 days getting beat up, sore (hands) and frustrated. Ideally, I will return to the drum and feel like I have learned something - it has not yet happened. (The moral of this story is that 3 days is not enough time to learn anything). Kopeyia was very interesting, though. It is a small village of about 250 people and it has no electricity or running water (sponge baths, lanterns, mud huts and an outhouse). It is in the Volta region, which is Ewe (where my name is from). Throughout my stay, a number of older people looked at me in confusion. They could see by my dress and hear by my speech that I was American, but they commented that I had strong Ewe features and I looked quite Ewe. When I told them my name, they embraced me and said that I was Ewe, welcome home and proceeded to call me by my last name and not by Anthony. In fact, most people called me either Kwesi (male born on Sunday) or Delaney during my time there. I spent about 3 and 1/2 days in the village of Kopeyia at the Dagbe Cultural Center attempting to learn traditional drumming. It was very hard for me. I had two 2-hour lessons per day and I am horrible. The hardest part for me is the timing because the entire sound is based on the offbeat. American music is rooted in the downbeat and the 4/4 timing. Here, everything is polyrhythmic and played OFF of the downbeat and in 5/6 or 6/8 time. I have equated it to snowboarding - when I first started snowboarding, I spent 3 days on the slopes falling down and getting beaten up, sore and frustrated. I later came back to it and enjoyed myself. Here, I spent 3 days getting beat up, sore (hands) and frustrated. Ideally, I will return to the drum and feel like I have learned something - it has not yet happened. (The moral of this story is that 3 days is not enough time to learn anything). Kopeyia was very interesting, though. It is a small village of about 250 people and it has no electricity or running water (sponge baths, lanterns, mud huts and an outhouse). It is in the Volta region, which is Ewe (where my name is from). Throughout my stay, a number of older people looked at me in confusion. They could see by my dress and hear by my speech that I was American, but they commented that I had strong Ewe features and I looked quite Ewe. When I told them my name, they embraced me and said that I was Ewe, welcome home and proceeded to call me by my last name and not by Anthony. In fact, most people called me either Kwesi (male born on Sunday) or Delaney during my time there.

After Kopeyia, I went to a city called Kumasi in the Ashanti region. I didn’t like

Kumasi. It seemed to be very busy and dirty and thick with pollution (although the night life seemed happening). It seemed like an industrial city, like the African version of Detroit (however, I have never actually been to Detroit). I also got very sick there (what goes down must come up) and stayed sick for almost a week. The highlights were woodcarvings, traditional, old Kente cloth, and Adinkra cloth. The lowlights were getting sick and the pollution (it may have just been particularly bad those few days, but the pollution was literally as thick as fog and people were driving with their lights on). While I was choking from the pollution, I wrote this poem (again, unfinished)

The Door of Return

If you cut me open

And reached inside

You could squeeze liquid diesel

From my lungs.

Take a butter knife

And scrape the red dust

From my arms and ears

And the space between my toes.

Find some warm water (good luck)

And see if you can wash the $

From the small of my back.

I will help you

And we’ll scrub together

I will bend backwards

And hope that you can support me.

Odd, isn’t it?

You supporting me.

And you thought it would be the other way around. |

An Email

Sent: Saturday, August 11, 2003 5:48 PM

Subject: Preparation

Friends,

In two days I will leave Ghana. It’s all a bit weird now. I’m sick of running around and haggling for prices on everything. I am sick of buying and spending. I’m road weary and tired of traveling. I’m not necessarily ready to leave Ghana, but I am ready to leave this situation: the lodging, not working, unexplained expectations, spending, spending, spending, etc.

Since I have been here, I’ve made a number of decisions (that I may or may not accept once I get back to my normal life). I want to go back to school and get a PhD in African American Studies

(UC Berkeley, Howard or U.W.). I want to find a different apartment near the lake in Oakland. I want to begin writing a personal narrative/autobiographical novel. I want to reignite the Caliban Foundation and begin a new program called Sankofa that financially supports a cultural youth program in Ghana and also focuses on helping African American youth connect with their African heritage - hopefully raising enough money to organize a small trip to Ghana for Black youth. I want to buy a plot of land in Ghana and start building a house. I want to be the next Bob Marley (this is big - although I’ve always liked writing and making music, I always felt that being a writer or a musician was inherently selfish and you were not doing anything to better the world around you (like teaching). For a number of deep reasons, this trip has shown me the value of working with one’s talents, whatever they may be. And that giving yourself to your talent is essential and not selfish, especially if you use your talent to better the world. It is amazing how life-changing Bob Marley’s lyrics are to people. At the University of Oregon (where I went to school), Bob Marley is just a Frat cliché - Everybody has Legend and you can’t go a day without seeing a bunch of tie-dyed, white hippies swaying to “No Woman, No Cry,” “Three Little Birds” or “Redemption Song.” It took me a trip to Jamaica and a Trip to Africa to finally accept (not to see, but to “accept”) that Bob Marley exists on a different plain of understanding. Maybe it was my interest and gravitation to Fela Kuti and Highlife that finally brought me back to Bob and the power of radicalism through art.)

Well, anyway... I’m rambling. I think that I am fortunate to come back from this trip a different man. I have felt that I have just been spinning my wheels in California without any strong direction. I’ve just been going with the flow of things. I think that this trip came at a changing point in my life. A point where I was feeling anxious for something different, something important. I’m not trying to say that I’ve found that here in Ghana. I’m not trying to say that I have a “whole new lease on life.” I guess I’m just trying to say that I have been standing at the junction for a few years now, and this trip has allowed me to accept that there are other roads (not to “see” that there are other roads, because they’ve always been there, but to accept that they are real and tangible and that there is value in letting go of the apron strings and venturing down those roads without a trail of breadcrumbs for that time when life gets tough). So, I’m not somebody else, now. I’m not coming back to change my name, sell all my possessions and live on a diet of plantains and pineapple. I am still me. I guess I am just more of me.

Well, this will probably be my last transmission from the motherland. I look forward to seeing all of you at some point in the near future.

-Kwesi Anthony

And then I left. Just like that, it was over. Life changed the minute I boarded the plane. Somewhere between Accra and London my clothes dried out completely (Ghana is very humid) and Ghana had left me just that quickly. I now have memories, four 90-minute videotapes, Kente and carvings. I am now struggling to fit back into a system where most people don’t look like me. I am now struggling to fit back into a system where disposable income and convenience are abundant. I have so easily fallen back into a system where hot water and bathrooms are assumed. Life is life, I guess. Whenever I would ask my friend Dada (a Ghanaian

drummaker) how it was going, he would answer: “It goes the way it’s supposed to go.” For good or for bad, things go the way they are supposed to go. Somewhere else, I heard someone say: “If you haven’t gotten where your going, you’re not there yet.” I guess our only job is to accept the way things go and try to understand, believe and focus on where it is we’re trying to go. Maybe I’m just trying to actually “see” everything in my life so that I can understand what’s real and what’s not.

Anyway, thanks for reading.

-Kwesi Anthony

Anthony@calibanfoundation.org

|