|

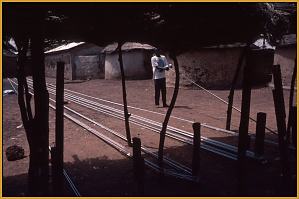

There is no warp beam on the

back of the West African strip looms—only what is called

by Eric Broudy (The Book of Looms) a "diverting

bar". The warp travels over

the diverting bar and stretches its full length across the

compound’s courtyard. The warp is then tied to a weight or

stone—this weight both anchors the warp and maintains even

tension. This weight is called a "drag Stone". As

the weavers weave and pull the warp forward the stone is

dragged along the dirt towards the weaver. In many villages

you can see the path the stone makes as it is dragged closer

and closer to the loom.

The warp is prepared either

in the courtyard of the compound, out in the streets of the

village or any place where there is enough space. If space

is a problem—as in some towns in Mali, the professional

Warp Preparer will wind the warp around his house. However,

when there is enough space poles three feet in height are

used. They are hammered in the dirt and spread evenly apart.

A forked tree branch is sometimes used to maintain the

cross. For an Ashante man’s cloth (or toga) which is

usually 24 strips wide and approximately 3 yards long, the

warp has to be 32 yards long. The warp poles are arranged in

any manner that is convenient to obtain this warp length.

The Warp Preparer—which is an occupation akin to that of

the weaver—knows from memory the required length and color

rotation for a specified pattern.

After the warp is prepared,

it is wrapped onto large bobbins, which are then placed on

the tines of a bobbin carrier. This bobbin carrier is called

in Ashante "menokomenam", which means

"I walk alone". From the bobbin carrier the warp

is transferred to the shuttles.

Treadles are also simple in

construction. Twine is tied to the harnesses—at the end of

the twine are knobs which are made from a calabash gourd.

These knobs are placed between the toes of the weaver. As

the weaver’s feet move up and down so do the harnesses. In

Mali a knot is made at the end of the twine and this knot is

placed between the weaver’s toes. In both instances the

function is the same—the weaver’s feet become the

treadles. Treadles are also simple in

construction. Twine is tied to the harnesses—at the end of

the twine are knobs which are made from a calabash gourd.

These knobs are placed between the toes of the weaver. As

the weaver’s feet move up and down so do the harnesses. In

Mali a knot is made at the end of the twine and this knot is

placed between the weaver’s toes. In both instances the

function is the same—the weaver’s feet become the

treadles.

Weaving is done outside and

is a social activity. Small sheds or fronded roofs are built

to protect the weavers from the heat of the sun. Shade from

trees also can protect the weaver from the mid-day heat. As

I wandered through a village I would see weavers working

together with their long warps stretching far into the

compound. Up to three yards of woven fabric is made during

one day’s weaving. At the end of the day the weaver

dismantles his loom and takes it inside the house for the

evening.

A weaver I met in Timbuktu

(Mali) demonstrated for me the ease of dismantling a loom.

He was weaving in a guildhall in the city of Timbuktu. I

arranged to meet with him at the end of the day—he wanted

me to meet and have dinner with his family. He took his

warp, the reed and woven fabric, wrapped them into a ball

and placed them into a bag. He then untied and collapsed his

loom, bound the loom pieces together, put the loom on his

head and shoulders and carried it home. A weaver I met in Timbuktu

(Mali) demonstrated for me the ease of dismantling a loom.

He was weaving in a guildhall in the city of Timbuktu. I

arranged to meet with him at the end of the day—he wanted

me to meet and have dinner with his family. He took his

warp, the reed and woven fabric, wrapped them into a ball

and placed them into a bag. He then untied and collapsed his

loom, bound the loom pieces together, put the loom on his

head and shoulders and carried it home.

|